ARCHITECTURE AS AN INTERSECTION:

MOBILITY IN DOWNTOWN KAMPALA

Thomas Aquilina

︎︎︎

Thomas Aquilina

︎︎︎

Introduction

This essay explores everyday mobility between colonial infrastructures and contemporary commercial spaces as essential for developing a method of architectural practice for Kampala, Uganda. The city is characterised by an incessant movement of bodies, objects and vessels.

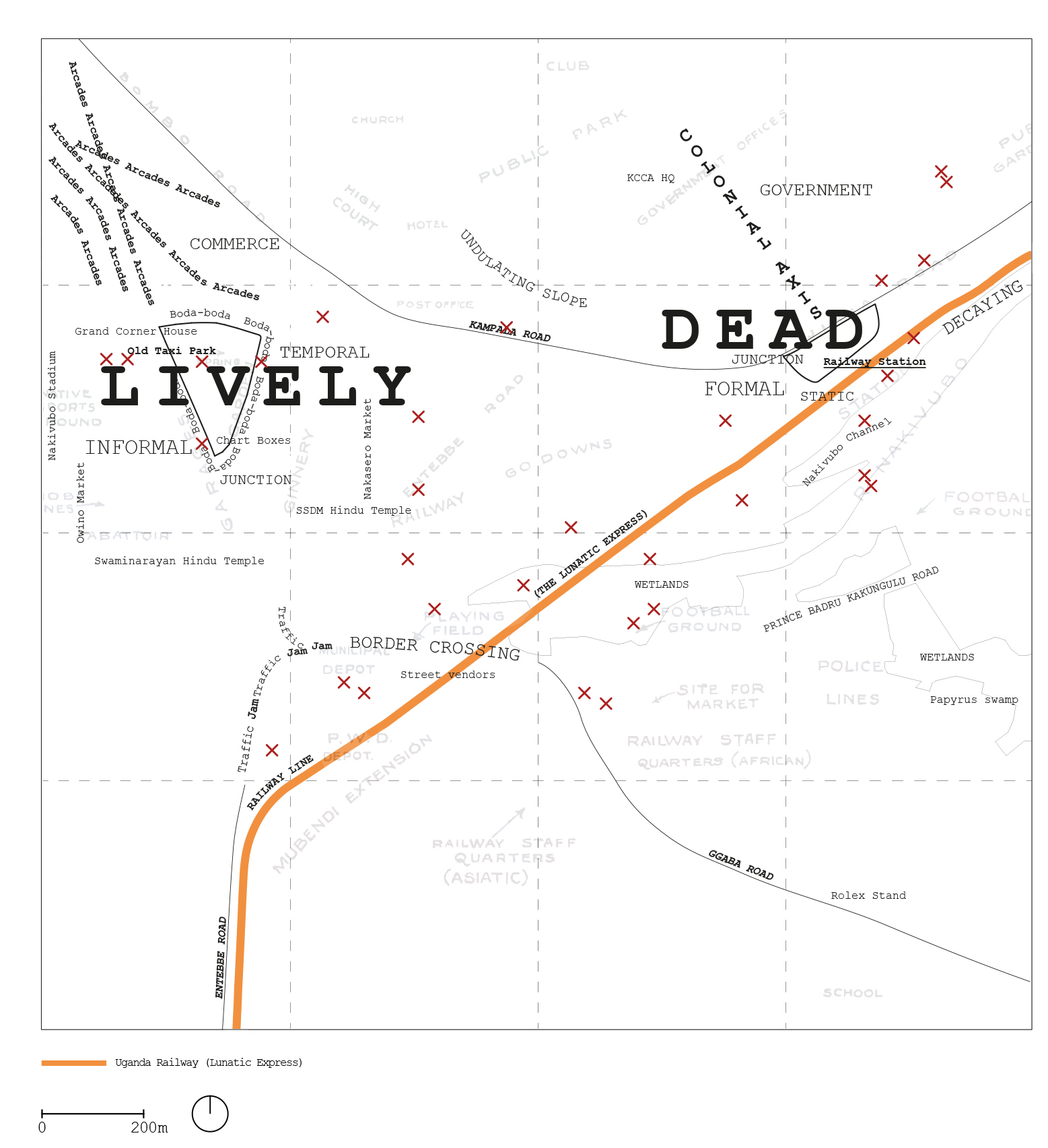

Beyond the realities of a city undergoing runaway urbanisation, this essay explains how downtown Kampala is a confluence of specific historical trajectories inscribed into its urban fabric and everyday perpetual motion. In the contemporary moment, residents rely on the ubiquitous motorcycle taxi agents, called boda-bodas, to move and navigate across the city. These motorcycles seem to typify broader senses of mobility in the city: never far away, endlessly circulating, easily navigating the obstacles of traffic and seemingly outside of temporal limitations. The railway line and shopping arcades are fixed spaces that illustrate how people place their own desire lines across the city. These points provide evidence to explore the kinetic organisation of the city and how to define the boundaries of an architectural mandate.

In many spatial commentaries, Kampala is overlooked because of greater interest in its neighbours, such as the megacity of Nairobi or the apparently more modern city of Kigali. Although Kampala is seemingly less visible, historians, artists and architects are increasingly acknowledging it as an equally important protagonist of Southern urbanism. Important readings of the city have advanced an understanding of Kampala in conversations about African modernism and mobilities.3 My own fieldwork between 2013 and 2017 investigated Kampala as an important site of contemporary urbanism and unmaking of colonial histories. This essay is a result of that research, as a way to understand the city’s past in the present and imagining a future form of urbanism.

Whilst mobility is a critical feature of many cities in Africa, it is especially remarkable in Kampala because the city grew as a place of commerce alongside the preserved realm of the Buganda Kingdom. Three distinct forms of urbanism show how mobility was differently embedded into Kampala’s past. First, the era of a mobile indigenous city, moving from hill to hill, and characterised by mobility and a mixing of spatial functions. Second, the static city emerges in this context as an imposed colonial urbanism, insisting on segregated spaces and single-use built form. Third, the more dispersed Asian bazaar city controls downtown with Indian migrants overseeing an incremental growth of markets and vernacular dukas.4 Across these three forms of urban development, the city’s hilltops are being used differently. From the time of independence in 1962, these mobile and static manifestations begin to overlay and continue to be shaped by diverse influences. For the focus of this essay, Nakasero Hill, the site of downtown, becomes critical to this further analysis.

Historical Collisions: between railways and arcades

Today, the legacy of intersecting spaces is not only retained but also reinvented in downtown Kampala. Across all the examples for making urban life, two domains stand out as sites of possibility to take the city in different directions: the single railway track and series of arcades. In both comparable and contrasting ways, they appear to represent separate stages of the city’s composition and, at present, define Kampala’s simultaneous growth and decay.

Previously a symbol of established and timetabled mobility, the railway infrastructure in Kampala now exists in an almost dead state. The single railway line, running in an east-west direction, slices through downtown as an impermeable colonial relic. Although the railway once served as Uganda’s lifeline, since the 1970s, traffic was gradually lost to road transport as investment and maintenance in track and rolling stock declined and the Mombasa-Kampala route was decommissioned.5 The Kampala Railway Station is now in limited use as an office for Rift Valley Railways, who privately operate a handful of freight trains daily. Today, at the eastern end of downtown, the station remains an iconic vestige of colonial architecture. The building anchors the only formal set piece of planning in Kampala: the station’s front door forms an axis along Nakasero Hill with the parliament building.6 The station is a structure of brown sandstone, a two storey, horizontal volume. Since its construction in 1940, it remains almost unchanged in its present condition except for minor alterations and new paintjobs. The alteration drawings, made between 1957 and 1965, depict and symbolise colonial rule: annotations for segregated rooms and entrances, notes for compliance with British Standards of Practice and details on the pattern roof tiles from Mangalore, India. The floor plans disturbingly reveal excluded accommodation for Europeans (Upper Class), Asians and Africans (3rd Class). In its current limited usage, this enforced separation is not easily noticed, but is embedded within the layout and fabric of the building.

The railway reserve is a substantial area and legally stipulated as a 30.5m wide corridor passing through downtown. In an absence of authoritative control, these physical remnants of colonialism are repurposed with temporary vegetative and human occupancy. Street vendors, kiosk businesses, urban farmers and commuters gravitate towards the railway corridor: essentially now a slow-moving market space. The track has an unassuming presence in the city and everyday life has become integrated with the railway reserve. Intersecting the central topography of the city, the track has become an interstitial zone. At the same time, downtown has in recent years developed around this large railway reserve, a crumbling urban obstacle to be navigated and built around. Whether functional or not, the line continues to make its mark and highlight the long history of division. In the past, the British colonists planned for urban development on hills only north of the railway line and, whilst Kampala has since expanded exponentially in all directions, anything south of the line is still considered outside of downtown.

Life along the railway track could not seem further away from the inhabitation of the arcades. Despite their proximity in downtown, at first sight, the railway line is a static zone compared to the animated impression of the arcades. The latter appears as a space in motion, easily recognisable and where the physical fabric is constantly improvised. Meanwhile the once monumental railway is now inert and seemingly invisible. These sites expand on urban geographers Ash Amin and Stephen Graham’s assertion that the city “needs to be considered as a set of spaces where diverse ranges of relational webs coalesce, interconnect and fragment.”7 They are deeply embedded in the structure of the landscape even as they register mobility in different ways.

The modern arcades supersede the original Indian-influenced duka forms, replacing street-front shops with walk-through passages and endless runs of the same type of facade. The first kind of downtown arcade, Capital House, appeared in 1995 and was influenced by the design of Arabian malls.8 Subsequently, the precipitous building of arcades was adapted from this particular form and aesthetic, which accepts East-looking cities as a local aspiration. Most of these buildings are tall structures offering a vertical aspect to city life. They each follow a distilled aesthetic of characteristic elements of concrete columns, screen walls, air grills, painted and tiled wall finishes and distinct signage. Originally static urban zoning was reflected in the arcades, which each dealt in a specific product, for example, whole buildings dedicated to fabrics, stationery or motor-car parts.9

However, recently constructed arcades appear to be more hybrid spaces. The Grand Corner House, opened in 2012, is the tallest arcade with eleven floors. Internally it accommodates a variety of traders in small commercial units with each level divided by different products. Located on the corner of the Old Taxi Park (minibus terminus), the sloping character of the ground is reflected in the substantial level change at each end of the building. Indeed, the arcade relies on the high footfall from the adjacent terminus, with people often moving through its narrow passage, which extends the whole block and connects to adjoining arcades. This kind of circulation system has become useful for connectivity in the city, assisting pedestrian movement across downtown and away from boda-bodas that dominate the streets. These buildings are lively infrastructures as they absorb this activity and are a crucial medium and repository for the transitory, commercial culture of downtown.

Whilst the arcades and railway have in many ways facilitated a sense of space, it is also clear that mobility is impacted by impenetrable colonial fragments. However lunatic the intentions and exploitations of the British colonists, these palimpsests are not easily erased from the surface. At the same time, the everyday conditions and practices that have since become ubiquitous across downtown appear to collide, at times abruptly, with these inherited obstacles. But rather than see this collision as a problem to resolve, it can become a productive resource that enable different approaches to urban development compared to the dominant visions taking hold in the city today. The kinetic atmosphere of Kampala is generated by the very intersection of static and mobile manifestations.

Criss-crossing, Convertibility and Convergence

This section synthesises the relationships between the railway and the arcades. Such relationships are mapped out in three parallels of mobility: the crisscrossing of paths, the convertible use of space and points of convergence. In doing so it explores possible downtown futures, proposing alternative ways of thinking about intervening in this context.

First, these multiple crossings and everyday connections have become the very sustenance of these spaces. To crisscross the railway line and the ground floor of the arcade is not only an energetic shuffle between places, but also an overlapping and mixing of people as a social infrastructure. At the same time, whilst open and porous in form, these infrastructures invite movement, and contain a potentially volatile capacity. On the one hand the tracks with high foot traffic and arcade passages sustain the everyday, incremental transformations, whilst on the other hand they can be sites for explosive protests and contestation.10

Second, the dual potential of these spaces due to their convertibility makes them respond in particular ways to the passing of time on an everyday basis as well as in the long-term. The most recognisable example is the railway line used as a street. The ruinous quality of this conventional infrastructure invites appropriation by the loose cohesion of kiosks on one or both sides of the line and caters to the needs of the everyday traveller. In some cases, original functions coexist with secondary uses, such as the arcade as a watchtower, the Old Taxi Park as a vending marketplace and the matatu (minibus) rear window as an identity slogan. Convertibility is rooted in the historical narrative of the city, such as the Kibuga adapting their palaces into tombs after moving hilltops. This flexibility of space influences the culture and actions of the people who occupy it, and a similar process can be seen in the naming of the staple street-food ‘rolex’.11

Third, as points of convergence there must be reason to pause. In a way, the capacity to converge relies on the preceding two factors of crisscrossing and being convertible. As Njami notes “all movement has an origin”, and therefore it is useful to consider the source of attraction towards the arcades and railway.12 Both have knuckle-point intersections that channel movement and gather intense activity. They are conveniently located: the arcades exist in a symbiotic relationship to the matatu terminus, whilst the railway line is mutually integrated into the different forms of human habitation along the railway reserve. In a context where the outsider notions of public and private are inappropriate, the mutating and prevailing spaces of transport and commerce have emerged as alternative thresholds.

An Emerging Architectural Mandate

These distilled features interpret three ways in which mobility is embedded within the arcades and railway and, in doing so, capture a specific geography of downtown Kampala. They offer possible starting points for creating a design strategy that is well grounded in the historical and spatial contexts of the city. As they are encountered as part of the urban realm, the arcades and railway are encompassed as ‘infrastructural’ elements. This acknowledges the incompleteness of the city’s infrastructures, but also sees potential in this improvisation. To design for Kampala is inherently an improvised task.

Incorporating the learned lessons from downtown Kampala, it is necessary that any approach to architecture is mediated by an idea of mobility. Hence, this proposal suggests an architectural form to be convertible, to be a place of convergence and to ensure mandatory occupant crisscrossing. There is a certain amount of experimentation to be absorbed in these concepts and methods. If finely attuned to the dense dynamics of everyday life, however, the design can encourage an urban space of hybridity. Therefore, countering the current paradigm of urban development and infrastructural delivery, it will reaffirm and integrate the role of mutually supportive local microenterprises in the functioning of the city. At the core of a proposition is an idea of architecture as an intersection. In other words, in what ways can a building bring different spheres into contact and become a junction between people, objects, vessels, infrastructures and the city at large.

For a proposal to be convertible, it must look at its immediate environment and see what is recyclable. In this way, the proposal might present a speculative redevelopment of the colonial Kampala Railway Station instead of building a new terminus. The ground is already prepared for use and the retention and incorporation of the old station into a new design suggests an urban future through the repositioning of what already exists. The unchanged station plan since 1965 can be censored, edited and redrawn to integrate a programmatic mixture of spaces that encourage a local urbanity and reconnects the site with downtown. The proposal can therefore retain spaces for renewed railway operation whilst accommodating services for other local agent and transit services, particularly the recognition and integration of boda-bodas. In this regard, the currently idle station concourse can then be conceived as a civic room and, consequently, the building can be approached as the threshold of this edge in the city.

![Editing Kampala Railway Station ground floor plan [paper collage] © Thomas Aquilina](https://freight.cargo.site/t/original/i/86c328652aa806a58f2b8d6ea93f184b612080aa498cd472940bee9a6b360707/Editing-Kampala-Railway-Station-ground-floor-plan-paper-collage--Thomas-Aquilina.jpg)

For this redevelopment of the Kampala Railway Station to be a place of convergence, it can be imagined as a kind of hybrid: part station, part arcade. Although they significantly differ as urban types and represent separate functions of transport and commerce, the arcade exemplifies the patterns and practices of the urban everyday in downtown. Co-opting the arcade will help transform the station from a dead relic into a tangible, functioning urban building. This radical formulation as a sort of ‘metamorphosis’ can be influenced by Njami’s curatorial technique, which focuses on processes of deconstruction and forms of invented hybrids.13 The typological metamorphosis can be approached through a combination of arcade references inserted into the station. For example, the facade or floor plates can integrate a number of distinct local aesthetic ‘elements’: concrete columns, screen walls and air grills. The station can also be camouflaged in advertisement signage in the same way the arcades’ exterior or can be repainted with a distinct distilled colour palette from the arcades. These methods can create an atmosphere that is distinctive yet familiar, and can therefore attract ordinary life to the station.

If this blended architecture was to ensure mandatory occupant crisscrossing, the redevelopment can be imagined through a language of cuts. Influenced by the arcades, where the passages function like internal streets cutting through whole blocks of buildings, these incisions into the station’s colonial form can create new spaces and expose new elevations. These cuts can form new paths and routes through the station producing a supple, intricate form sustained by intense physical movement and a thickening of social engagement. They will also provoke a spatial and historic understanding of the station by exposing and disrupting colonial history. Therefore, the conservation and manipulation of the existing station is considered as an inventive rather than a constraining practice. In essence, this speculative hybrid can become a space of mixture, and reinterpret rather than remove the contemporary Kampala vernacular base.

These concepts for rethinking the future of Kampala Railway Station do not necessarily offer a resolution between all parties, but can instead provide an alternative imagining. It is essential to carefully tend to the city’s delicate, ordinary three-dimensional reality and not as a generic, foreign abstracted space. To see the city differently can be to see it as an architectural mandate; by approaching a design process through a form of editing, it is comparable to the role of the architect-curator. The juxtaposition of the past colonial and present emergent city can, indeed, collide with invention and experimentation. Hence, the station can be conceived as part of a rejuvenated transport system, but also as a prototype for possible architectures in downtown as well as part of the urban trajectory of Kampala. In a sense, the attempt to reimagine the Kampala Railway Station is to envision what downtown can be: a more hybrid, loose-fit and tolerant urban realm.

Themes:

Wounds of Ruptures, Spatial Claims

Methods: Archive, Counter-Cartrography

References:

[1] KCCA, ‘Kampala City Strategic Plan 2020/21 to 2024/25’ (Kampala: Kampala City Council Authority, 2020).

[2] KRC, ‘Developing World Class Standard Gauge Railway’ (Nairobi: Kenya Railways Corporation, 2015).

[3] Doreen Adengo, ‘Kampala: The Garden City’, in Urban Uganda: City Explorations and Life Expressions, ed. Laura Guzman and Maria Carrizosa (New York: The New School, 2014), 10–13; ‘Seven Hills: Kampala Art Biennale’ (Kampala, 3 September–2 October 2016); ‘African Mobilities: This Is Not a Refugee Camp Exhibition’ (Architekturmuseum der TU München, 26 April–19 August 2018).

[4] The original form of an arcade influenced by Indian-era buildings. Usually consisting of five rentable shops, a covered veranda and residential facilities at the backside.

[5] UNRA, ‘The National Transport Master Plan’ (Kampala: Uganda National Roads Authority, 2008).

[6] Jonathan Nsubuga, Interview with Architect, J.E. Nsubuga & Associates, interview by Thomas Aquilina, J.E. Nsubuga & Associates office, 12 August 2015.

[7] Ash Amin and Stephen Graham, ‘The Ordinary City’, Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 22, no. 4 (1997): 418.

[8] New Vision, ‘I’m Living My Dream’, New Vision, 4 May 2012.

[9] John Abimanyi, ‘Out Go the Markets, in Come Arcades, Our New Shopping’, Daily Monitor, 16 October 2011.

[10] Sam Waswa, ‘Teargas as Railway Reserve Squatters Protest’, Chimp Reports, 4 August 2014.

[11] A flip of an established consumer brand, recoined for the staple street-food. An omelette topped with cold tomato slices and salt, cooked and rolled in a chapatti.

[12] Simon Njami, ‘Chaos and Metamorphosis’, in Africa Remix: Contemporary Art of a Continent, by Simon Njami (Johannesburg: Jacana, 2007), 18.

[13] ‘Chaos and Metamorphosis’.

![]()

[i] For another piece on bodies and vessels in the contemporary city, see: AN EXTENSION OF DATA: THE NEW BLACK GOLD by Ibiye Campe

[ii] For another piece on on postcolonial space and imagining otherwise, see: EARTH / SATELLITE STATION / MAZOWE by Thandi Loewenson

Methods: Archive, Counter-Cartrography

References:

[1] KCCA, ‘Kampala City Strategic Plan 2020/21 to 2024/25’ (Kampala: Kampala City Council Authority, 2020).

[2] KRC, ‘Developing World Class Standard Gauge Railway’ (Nairobi: Kenya Railways Corporation, 2015).

[3] Doreen Adengo, ‘Kampala: The Garden City’, in Urban Uganda: City Explorations and Life Expressions, ed. Laura Guzman and Maria Carrizosa (New York: The New School, 2014), 10–13; ‘Seven Hills: Kampala Art Biennale’ (Kampala, 3 September–2 October 2016); ‘African Mobilities: This Is Not a Refugee Camp Exhibition’ (Architekturmuseum der TU München, 26 April–19 August 2018).

[4] The original form of an arcade influenced by Indian-era buildings. Usually consisting of five rentable shops, a covered veranda and residential facilities at the backside.

[5] UNRA, ‘The National Transport Master Plan’ (Kampala: Uganda National Roads Authority, 2008).

[6] Jonathan Nsubuga, Interview with Architect, J.E. Nsubuga & Associates, interview by Thomas Aquilina, J.E. Nsubuga & Associates office, 12 August 2015.

[7] Ash Amin and Stephen Graham, ‘The Ordinary City’, Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 22, no. 4 (1997): 418.

[8] New Vision, ‘I’m Living My Dream’, New Vision, 4 May 2012.

[9] John Abimanyi, ‘Out Go the Markets, in Come Arcades, Our New Shopping’, Daily Monitor, 16 October 2011.

[10] Sam Waswa, ‘Teargas as Railway Reserve Squatters Protest’, Chimp Reports, 4 August 2014.

[11] A flip of an established consumer brand, recoined for the staple street-food. An omelette topped with cold tomato slices and salt, cooked and rolled in a chapatti.

[12] Simon Njami, ‘Chaos and Metamorphosis’, in Africa Remix: Contemporary Art of a Continent, by Simon Njami (Johannesburg: Jacana, 2007), 18.

[13] ‘Chaos and Metamorphosis’.

[i] For another piece on bodies and vessels in the contemporary city, see: AN EXTENSION OF DATA: THE NEW BLACK GOLD by Ibiye Campe

[ii] For another piece on on postcolonial space and imagining otherwise, see: EARTH / SATELLITE STATION / MAZOWE by Thandi Loewenson

Thomas Aquilina is a London-based architect and researcher. Since 2017 he has worked for Adjaye Associates. He co-directs the New Architecture Writers (N.A.W.) programme and is a co-founder of publishing collective Afterparti. His work features in digital and print publications, as well as exhibitions and public conversations. Thomas is invested in building communities of radical thought and progressive practice. His on-going research ‘Loose-fit Infrastructures’ explores the everyday life of downtown cities through a synthesis of image and text.

︎ @thomasaquilina

︎ www.thomasaquilina.com

︎ @thomasaquilina

︎ www.thomasaquilina.com