ENTANGLED CLOTH(ES): OCEAN, EMPIRE, BLACK MATRIMONY

Lebogang Mokwena

︎︎︎

Lebogang Mokwena

︎︎︎

My doctoral research explores the visual narratives of authenticity invested in and mobilised through the shweshwe textile in contemporary South Africa. Shweshwe is a resist-dyed cotton fabric that is industrially manufactured in Zwelitsha township in the Eastern Cape province of South Africa. The textile is increasingly understood as an indigenous textile, principally associated with black women’s traditional rite of passage into marriage although with an ever-widening range of uses to mark a distinctly afrocentric South African sartorial aesthetic. However, for much of the 19th century and well into the first half of the 20th century, what we now call shweshwe was a copywritten calico blueprint produced in Lancashire, England, by the Calico Printers Association. Printed onto calicos made from American cotton, by the early 20th century, the British sought to establish cotton mills in various parts of the British Empire to reduce Lancashire’s reliance on American cottons. However, it is important to note that in the mid-19th century, virtually all the blue-print cottons that arrived in the Cape of Good Hope (modern day Cape Town) arrived with German missionaries who required black converts to acquire European dress as one of the key markers of the their Christianisation (read civilisation).

The above historical sketch of blueprint’s manufacture as well as its arrival and circulation in Southern Africa is fairly well-established in the academic and intellectual field.

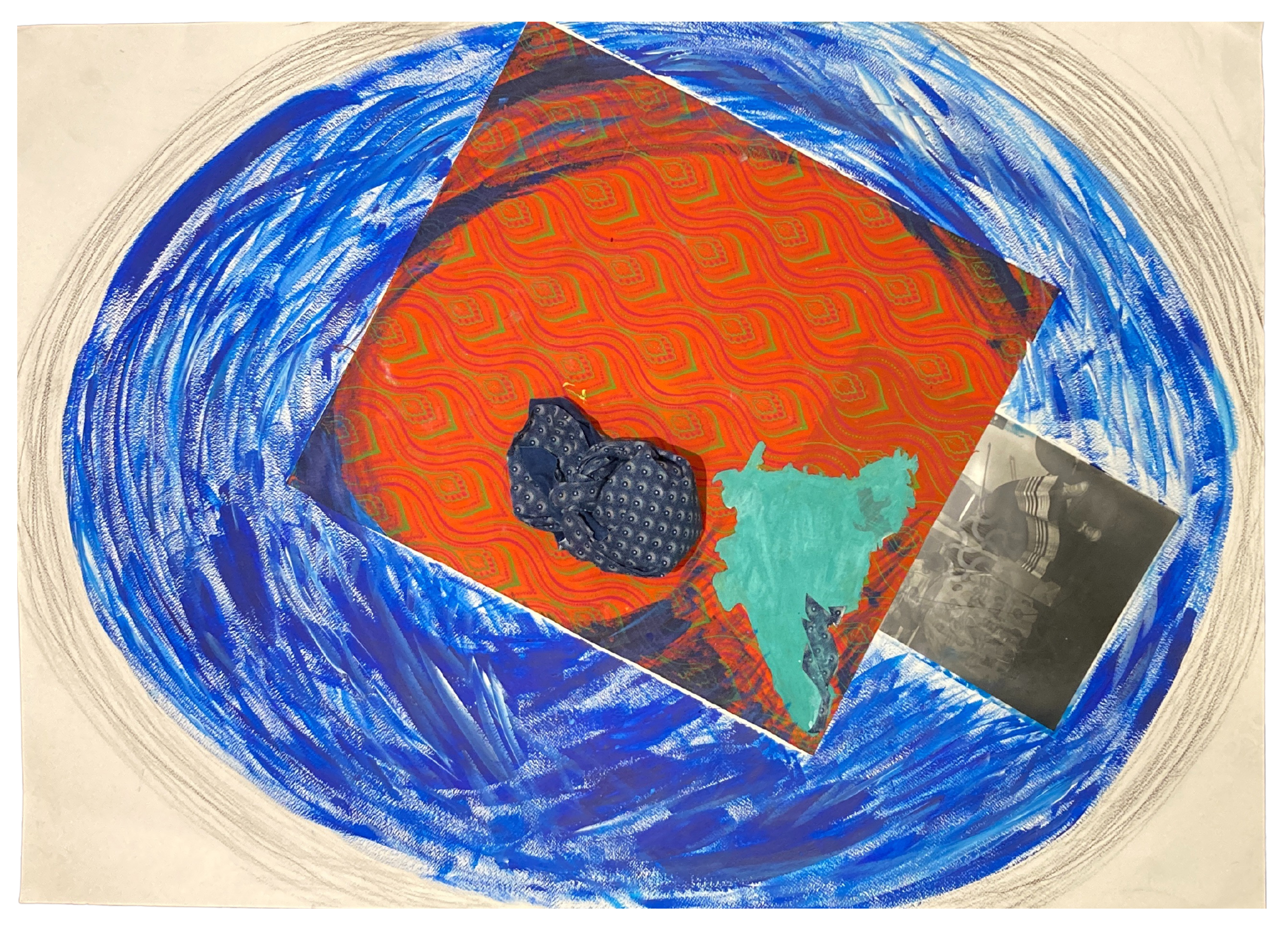

Tucked underneath the orange shweshwe canvas is an image of my mother and I sitting next to each other, both wearing dresses made from shweshwe. The photograph was taken on the evening of my traditional wedding ceremony. Because the image is printed onto a transparency sheet and in black and white, the viewer cannot tell that my dress is actually shweshwe and, specifically, the indigo blue-and-white that my family wears at our matrimonial ceremonies, which we call kgaka (the Setswana word for guinea fowl: our totem animal). My mother wore a different shweshwe print but also blue-and-white, as did all the women from my line of the family, who were dressed in either kgaka-print dresses and skirts, or some other variation of the indigo blue-and-white. When we were photographed, my mother, a staunch pentecostal Christian, was leading the singing of a hymn; setting the “‘spiritual” tone of an evening of live jazz music at my brother’s erstwhile art gallery and live-music venue called the African Freedom Station in Johannesburg. In my artwork, mine and my mother’s bodies are floating somewhere in the Indian and Pacific Ocean: I have resisted the temptation to draw the African continent anywhere on this work in the way that I have the Indian subcontinent, partly because wherever black African bodies move on planet earth, Africa is inscribed onto their skins; regardless of what we wear and how we wear it.

The orange textile and the photograph of my mother and I all float within a spherical rendition of earth’s oceans. In my brush strokes, I have tried to capture the Agulhas current (Indian Ocean current off the coast of Mozambique and South Africa) as well as Benguela current (from Cape Point to Benguela in Angola) as a way of bringing to the fore the Indian and Atlantic Ocean worlds in our thinking about the forces that have shaped contemporary South Africa.

Themes:

Spatial Claims, Interrogated Materialities

Methods: Ocean as Method, Bordering

![]()

[i] See Khensani De Klerk's use of fabric as a narration device in her piece: SPATIAL STORYTELLING: CONDUIT AND VESSEL

[ii] For a piece on movement and travel, this time of food and memory, see: A SOLUTION IS FOUND IN SALT AND SPICE by Fozial Ismail

Methods: Ocean as Method, Bordering

[i] See Khensani De Klerk's use of fabric as a narration device in her piece: SPATIAL STORYTELLING: CONDUIT AND VESSEL

[ii] For a piece on movement and travel, this time of food and memory, see: A SOLUTION IS FOUND IN SALT AND SPICE by Fozial Ismail

Lebogang Mokwena is currently a Prize Fellow and PhD candidate in the Sociology Department at the New School for Social Research, New York. Her scholarly interests lie at the nexus of cultural, historical, and global sociology, attending to the production, consumption, and circulation threads of the textile. Specifically, her research explores the authenticating power of the isishweshwe textile in the context of post-apartheid South Africa. Her contribution to the Disembodied Territories initiative is a visual meditation that grapples with the long history, global breadth, and intimacy of a textile that is most readily associated with South and Southern Africa.

︎ Lebogang Mokwena

︎ Lebogang Mokwena

︎ Lebogang Mokwena

︎ Lebogang Mokwena