INTERCOMMUNALISM AS ABOLITION: HUEY P NEWTON AND THE POLITICS OF BORDERS

Nivi Manchanda

︎︎︎

Nivi Manchanda

︎︎︎

“The police are here [….] to keep the status quo intact”:

“in America black people are treated very much like the Vietnamese people and any other colonised people.”

“The police in our community occupy us just like the foreign troops occupy territory.”

“The police don’t protect us just like the American troops destroy the Vietnamese people”

“The police protect property but we [black people] own no property”

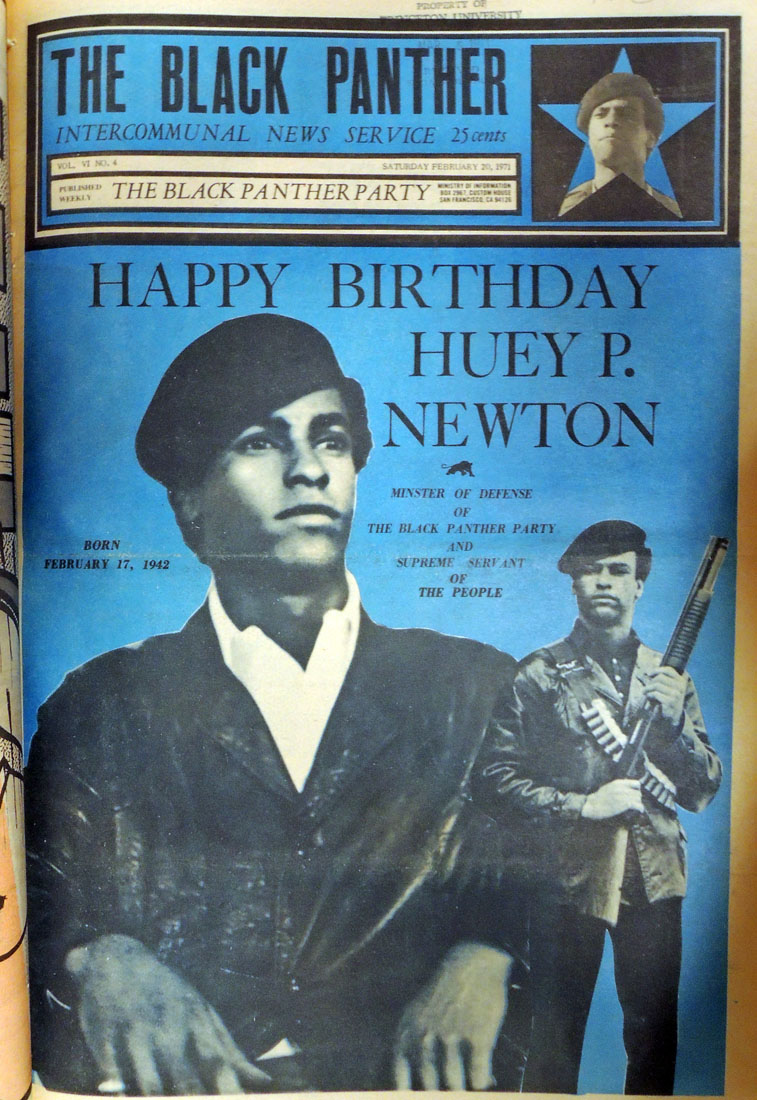

Dr Huey P Newton (1942-1989) is a canonical figure who has long exercised the imagination of the both the global anti-racist left, and the reactionary policy circles of Washington DC. He is best known as co-founder of the Black Panther Party in 1968 (along with Bobby Seale), which spawned a revolutionary and staunchly internationalist Black power movement.

‘Intercommunalism’ as a theory built on, but also diverged from some of his early work on the analogies between Black people in the US and colonized people across the ‘Third World’. For instance, Newton argued that in “America black people are treated very much like the Vietnamese people and any other colonised people”. Speech with video available here:

This was a common refrain for the Panthers who likened the police forces’ treatment of people of colour in the US to a colonial occupation. The US military forces in Vietnam, Newton posited, were indistinguishable from the racist police in the US – they both had “territory” and protected “property”. Likewise, Panther member Eldridge Cleaver reflecting on the violent suppression of the Watts uprising in 1965, wrote that the ‘blacks in Watts and all over America could now see the Viet Cong’s point: both were on the receiving end of what the armed forces were dishing out’. Additionally, and tellingly, he laments the lost opportunities for collective action and solidarity: ‘what all those dead bodies, on two fronts, implied. Those corpses spoke eloquently of potential allies and alliances’ (1968: 159; cited in Manchanda and Rossdale 2021).

The Black Panther Newspaper, which was also co-founded by Huey Newton was one prominent avenue through which the Panthers disseminated their vision of the USA, and the world at large. The artist and Panther activist Emory Douglas visually memorialised this tendency towards racial violence by the police at home and the military abroad in his iconic cartoon “it’s all the same”.

This comparison made imminent sense at the time: the world needed to unite against colonial oppression, whether that was at home against racialised policing or abroad against imperial (European or US) troops. However, as time went on and most countries in Asia and Africa had the reins of the government transferred from European colonisers to native authorities, a new way of conceptualizing this change was needed. The colonial analogy could not have the same resonance if Black people in the US remained ‘an internal colony’ but colonized people around the world divested themselves of their white overlords.

Sitting in prison between 1967 and 1970 (after being charged with the murder of a police officer), Newton reflected on this world historical moment and the ruptures and continuities inherent in it. Although he remained an ardent supporter of and campaigner for Palestinian statehood, and indeed other decolonial movements, he also tarried with the limits of the nation-state in the context of American intrusion, intervention, and invasion into the rest of the world both militarily but also financially and through other means. He first adumbrated his thoughts when he was released from prison to an audience at Boston College in 1970.

In this seminal speech, Newton outlined what he saw the reasons for the failure, or more accurately, the factors that inhibited the Panther’s project of wholesale transformation. In spite of mass mobilization and an appetite for radical change around the country, the material conditions for Black folk and poor people more generally remained largely the same. In the outside world, demands for statehood meant that many erstwhile revolutionary movements had to make compromises as they navigated Cold War geopolitics. Many in these movements became more cautious of their public pronouncements and wary of allying themselves with the Panthers, a vanguardist organization that demanded the explicit downfall of the US government (for more on this Malloy, 2017). Newton accounted for this plus ça change through his theory of intercommunalism. He argued that the US was a behemoth that controlled much of the world not through an army, but through a globe-spanning capitalist imperial enterprise. He imagined the United States as commanding an empire, but an empire of global capital that was dispersed and which often interpellated people of colour in its ambit. Without using the vocabulary of ‘racial capitalism’ (made popular by Cedric Robinson) or of ‘abolition’, Newton was an early theorist of both these conditions. ‘Abolition’ theorised by luminaries such as Angela Davis and Ruth Wilson Gilmore is primarily concerned with imagining and then bringing to life modes and ways of being and belonging that are not structured around the dictates of capitalism, racism, misogyny and ableism. Abolition is about the presence of alternative systems of welfare, of nurturing those rendered disposable by capitalist accumulation and neoliberal dispossession. In this alternative imaginary, structures of oppression especially carceral systems including prisons, migration regimes, border police forces are defunded and ultimately abolished and replaced by schools, youth clubs, community programmes aligned with an egalitarian, socialist and anti-racist vision of societal organization.

Likewise, Newton was a canny observer and theorist of the ways in which capitalism was shot through with racism. His theory of intercommunalism was ultimately an articulation of the mutual implication of race with class. In this account, as intimated above, the United States oversaw a ‘reactionary intercommunalism’ – the melding together of the world overseen by greedy financiers, the transnational capitalist elite in cahoots with the US state. The condition was racial capitalism: the inextricable and intertwined project of racism and capitalism across borders. The antidote for Newton was ‘revolutionary intercommunalism’ – a studied and diligent commitment to, and cultivation of, global solidarities that challenged the retrogressive status quo. Territory remained important for revolutionary intercommunalism, Newton’s new revolutionary movement was to be built on liberated territory. Decolonisation and the end of settler colonialism remained an important step, but it was not enough. In his own words: ‘It is true that the world is one community, but we are not satisfied with the concentration of its power. We want the power for the people’ (2019: 187). The retreat of the state must therefore be met with the cultivation of new forms of community, and new forms of relations with other communities subject to empire, en route to ‘a place where people will be happy, wars will end, the state itself will no longer exist, and we will have communism’ (Newton 2019: 188).

Although this revolutionary potential was never realised, given internal Party factionalism and a concentrated effort by the US state to repress by any means necessary the reach of the Black Power movement, Newton’s revolutionary intercommunalism is a clearly delineated abolitionist project. It necessitates the defunding of policing and racialised surveillance globally, and in its place demands the presence of a gamut of equitably distributed welfare projects. The Black Panther Newspaper had the tagline ‘intercommunal news service’ and it was already working towards this goal through its pregnant imagery and its often biting news reporting.

In sum, Newton’s intercommunalism which emerged from Black Power organizing and Third World solidarity (including with Vietnam, Algeria, Angola, and Palestine) is prophetic in its wrestling with questions of borders, abolition, and racial capitalism.

His emplacement of policing at home in a longer lineage of military actions and counterinsurgency abroad is emblematic in its analysis of mobile and racialised bordering practices. He also dislodged the then popular notion that anti-colonial nationalism was the antidote to Euro-American empire, but at the same time managed to question the legitimacy of a borderless world in which racial capitalism was the only currency. Newton’s ideas resonate with Ruth Wilson Gilmore’s apprehension of “freedom as a place” and explore the promise of a rupture from Eurocentric conceptions of time and space. Freedom as place is a commitment to unfettered lifeways that go beyond the place-making and delimited geographies of detention, deportation, and incarceration that are said to define the present. As opposed to these demarcated spaces of confinement, freedom-making pivots towards and invokes the emancipated horizons already made possible by communities of colour organising against disenfranchisement and the ravages of capitalism. Finally, these ideas can help disrupt dominant understandings of boundaries and European territoriality. Indeed, Newton anticipated the diminishing import of state boundaries and the insufficiency of national independence in a world where “communities under siege” could no longer look towards the apparatus of the nation-state as a vehicle for freedom or salvation. Instead non-statist avenues that were committed to the annihilation of capitalism and racism around the world needed to be explored and global networks along these aims needed to be forged. This different conception of space does not automatically think of the ‘third world’ in general, and Africa in particular as synecdoche for oppressed, and has an overtly liberationist, anti-capitalist, anti-racist underpinning. In the current conjuncture, riven as it is with climate catastrophe, flagrant racism, transphobia and revanchism, it opens new avenues for trespass, transgression, and global solidarity.

Themes:

Premonitions of Bodies,

Spatial Claims

Methods: Archive, Sonic

References:

Manchanda, N. and Rossdale, C., 2021. Resisting racial militarism: War, policing and the Black Panther Party. Security Dialogue, 52(6), pp.473-492.

Newton, H., 2019. The New Huey P. Newton Reader. New York: Seven Stories Press.

![]()

[i] On internationalism and contemporary Black struggle, read: FROM MINNEAPOLIS TO DESSAU, FROM MORIA TO TRIPOLI, FROM THE SHORES TO THE LAND AND THE SEA: GLOBAL GEOGRAPHIES OF ABOLITION by Vanessa E. Thompson

[ii] For more on resisting carcerality and the diaspora, read: AGAINST THE COLONIAL CARCERAL DIASPORA by SM Rodriguez

Methods: Archive, Sonic

References:

Manchanda, N. and Rossdale, C., 2021. Resisting racial militarism: War, policing and the Black Panther Party. Security Dialogue, 52(6), pp.473-492.

Newton, H., 2019. The New Huey P. Newton Reader. New York: Seven Stories Press.

[i] On internationalism and contemporary Black struggle, read: FROM MINNEAPOLIS TO DESSAU, FROM MORIA TO TRIPOLI, FROM THE SHORES TO THE LAND AND THE SEA: GLOBAL GEOGRAPHIES OF ABOLITION by Vanessa E. Thompson

[ii] For more on resisting carcerality and the diaspora, read: AGAINST THE COLONIAL CARCERAL DIASPORA by SM Rodriguez

Nivi Manchanda is Senior Lecturer in International Politics at Queen Mary University of London. She's interested in the politics of race and colonialism, and questions of borders, space, and abolition. She's the author of Imagining Afghanistan: the History and Politics of Imperial Knowledge (Cambridge University Press, 2020) and co-editor of Race and Racism in International Relations: Confronting the Global Colour Line (Routledge, 2015).

︎ QMUL

︎ QMUL