MAINTENANCE: AN AFRICAN PHILOSOPHY OF DESIGN

Mário Barros

︎︎︎

Mário Barros

︎︎︎

Themes: Spatial Claims, Interrogated Materialities

Methods: Intimate, Archive

![]()

[i] To read more about work, design and everyday objects, see: HERITAGE WORK AS SPECULATIVE FICTIONby Omar Berrada & M’barek Bouhchichi

[ii] Also read Olivia Umurerwa Rutazibwa’s ENGAGING NARRATIVE EPISTEMIC BLACKNESS

Methods: Intimate, Archive

[i] To read more about work, design and everyday objects, see: HERITAGE WORK AS SPECULATIVE FICTIONby Omar Berrada & M’barek Bouhchichi

[ii] Also read Olivia Umurerwa Rutazibwa’s ENGAGING NARRATIVE EPISTEMIC BLACKNESS

I never knew how to answer the question ‘What do you want to be when you grow up?’ The activities of the physician, the teacher or the engineer – the common choices of the so-called dignifying professions in society – did not have much to do with my daily life. I could not blindly aspire to follow an abstract model without first considering the tangible models – my parents – who provided me with a unique look at everyday things.

Everyday things are often overlooked. Those little things that make life functional, sometimes even more appreciated, are commonly underrated in modern society. Just think about the pay, respect and protection given to domestic workers or the general categorisation of lower skilled work attributed to blue-collar jobs.![]() i

These are exactly the professions my parents have held from a young age, and there is nothing unskilled about them. It has always been clear to me that it is all about care and, undoubtedly, pride in a job well done.

i

These are exactly the professions my parents have held from a young age, and there is nothing unskilled about them. It has always been clear to me that it is all about care and, undoubtedly, pride in a job well done.

Everyday things are often overlooked. Those little things that make life functional, sometimes even more appreciated, are commonly underrated in modern society. Just think about the pay, respect and protection given to domestic workers or the general categorisation of lower skilled work attributed to blue-collar jobs.

Allow me to provide some context. My parents are from Boavista – an island of the Cape Verde archipelago on the West African coast. They were born and raised in Boavista until they joined the inevitable diaspora. The basis of Cape Verdean society is matriarchal, and although there are strong roles attributed to men and women, the contribution of one is as equally important as that of the other. There is an underlying notion of complementarity and unity established with the concept of maintenance.

I was born and raised in Portugal, on the western coast of Europe, until I joined the inevitable diaspora. When I mention ‘everyday things’, I am mostly referring to the relationship between people and objects and how this was transmitted by my parents during my upbringing. Objects define many aspects of our relationship with the world. Objects have the power to transform a house into a home, create comfort by solving a need, or even change our mood when producing a certain ambience. The relationship between people and objects is always dynamic. We manipulate objects to adapt to our context by personalising something that serial production cannot cover, and we must maintain them if we want them to last. I learnt these and other ideas from my parents through direct observation, instruction and stories. With time they became crucial in my relationship with objects. These ideas are still relevant today in my work as an educator and researcher in industrial design.

I was born and raised in Portugal, on the western coast of Europe, until I joined the inevitable diaspora. When I mention ‘everyday things’, I am mostly referring to the relationship between people and objects and how this was transmitted by my parents during my upbringing. Objects define many aspects of our relationship with the world. Objects have the power to transform a house into a home, create comfort by solving a need, or even change our mood when producing a certain ambience. The relationship between people and objects is always dynamic. We manipulate objects to adapt to our context by personalising something that serial production cannot cover, and we must maintain them if we want them to last. I learnt these and other ideas from my parents through direct observation, instruction and stories. With time they became crucial in my relationship with objects. These ideas are still relevant today in my work as an educator and researcher in industrial design.

Maintenance, however, is not just a part of the relationship with objects but also a crucial element regarding human relationships. Maintenance is what enables life – natural or technical – to withstand time.

For my mother, maintenance is the cornerstone of domestic activity. She has always worked as a domestic worker, and I have always heard her say, ‘I am a domestic’. She defines herself by what she does both professionally and at home, in a meticulous, almost obsessive way. Even though she defines herself by the work of care that upholds a household, the caring and maintenance she does goes beyond the confinements of the home.

For my mother, maintenance is the cornerstone of domestic activity. She has always worked as a domestic worker, and I have always heard her say, ‘I am a domestic’. She defines herself by what she does both professionally and at home, in a meticulous, almost obsessive way. Even though she defines herself by the work of care that upholds a household, the caring and maintenance she does goes beyond the confinements of the home.

Human relationships and their memory are kept alive through oral tradition – remembering and telling how things happened and keep happening. The past blends into the present and provides a sense of belonging within a larger community that is spread out around the world. Relationships are nurtured from a distance over the telephone, through letters and, before that, by telegrams for reporting unfortunate moments of life. Even today, I know what is happening with family members in Cape Verde, France, Italy or the US more easily than on social networks and, undoubtedly, in a more illustrative and human way. These and other fragments of life are narrated with crafted spoken words and dynamic performances. My mother shifts from passive narrator to participant to the point of view of a specific person. She even provides details of the background, all in such a natural way that I only realised it after more than thirty years. Sometimes the selection of a story has a greater purpose, personalised to the specific moment or told to be digested in the future. The past is vividly transformed into a permanent present where memory and culture are passed from generation to generation.

I can affirm that every corner in my parents’ home has been cleaned or ordered for technical maintenance by my mother. She is both the expert and the gatekeeper. There have always been various types of domestic activity, and she coordinates who participates, when, how and what they are to do. Some activities I just watched while she was doing them; for some, even if I wanted to participate, I could not. Others, I simply had to do them. To be able to do them, a certain level of mastery was mandatory because ‘if you are to do this, you must do it well; otherwise, it is not worth doing it’. This involved a step-by-step explanation of the entire procedure. It should be noted that explanation, doing and exemplification were not separate activities; they were organic. Washing the dishes, for example, started with ‘open the lower cupboard door and remove the yellow sponge from the container and the dish soap’. After all those steps, it ended in the reverse order.

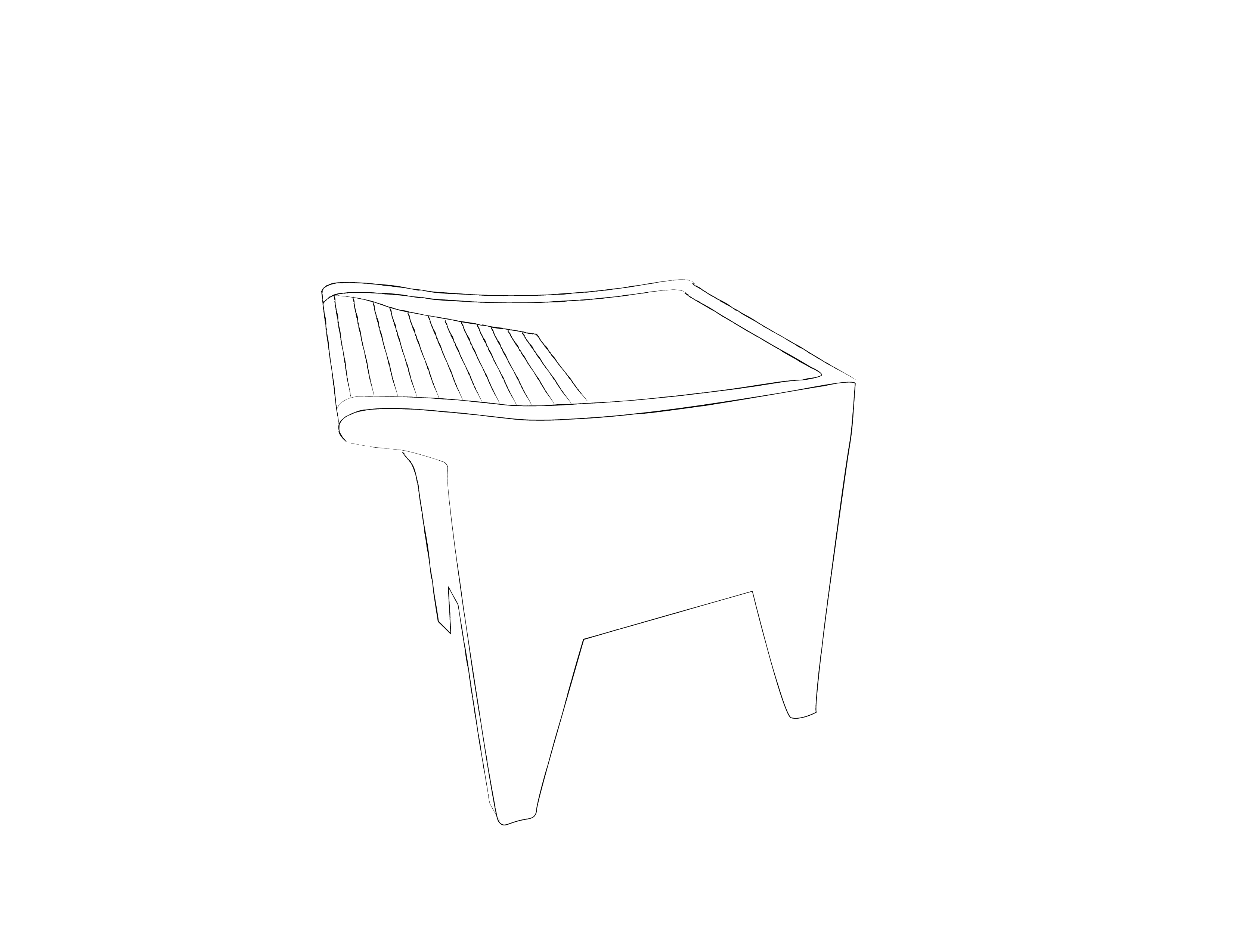

Other domestic activities were collaborative, such as unpacking groceries. Goods were transferred from the industrial packaging to home containers and stored right on that shelf – not that one, the one above. There were also the seasonal ones, like deep cleaning the living room, emptying cupboards, disassembling some of them, cleaning the carpet and painting the room. This was usually done on a clear summer day during the summer holidays, with music in the background. The whole family would take part, and in the end, satisfaction came in the form of a new room layout. It was like playing a living matching puzzle, taking parts from here to put there, in spaces previously prepared for temporary storage. Things that were rarely used or seen were revived by shared memories of past occasions. In hindsight, the organisation and planning was cogitated only internally and told on the go. The role of memory, short and long, is paramount.

Memory is what enables information to be stored, retained and communicated. In the relationship with objects, memory can relate not only to meaning, like the one described above, but also to function. Maintenance is a way to relate to the functional memory of objects.

![]() ii

ii

There is a spectrum of maintenance that starts with regular cleaning, goes on to repair and ends up with the scrapping of parts for a new continuum. Maintenance is part of the relationship with objects that enables them to last. Technical maintenance is routine consultation, while repair is life-saving surgery when function goes wrong.

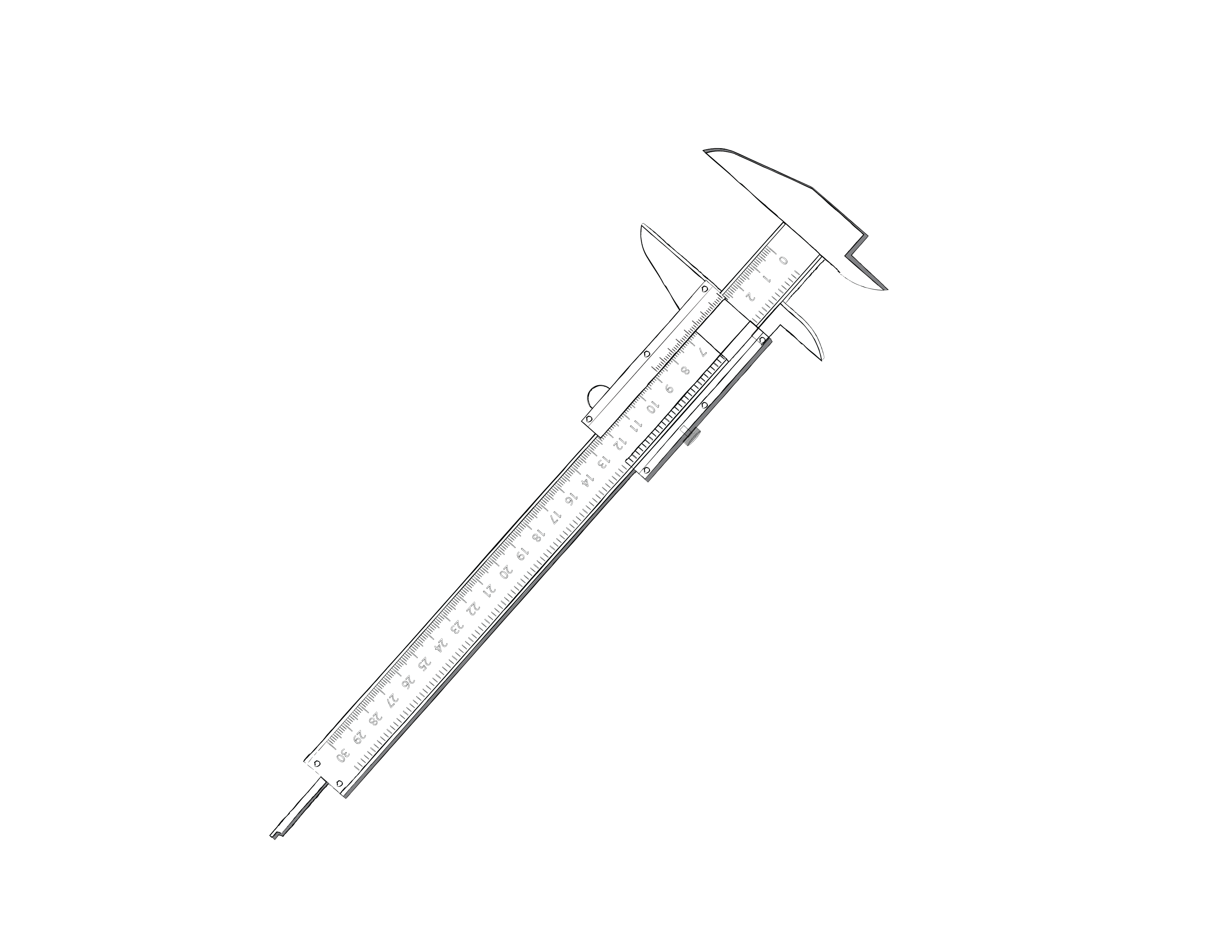

Technical maintenance and repair are part of my upbringing due to my father. Working as a ship mechanic meant that there was no difference between maintaining a part or an entire infrastructure, as both are determinants of good functioning of the system. At home, oiling a sewing machine, defrosting the fridge, changing the gas hose, repairing any broken appliance and so on were just normal aspects of daily life. The work of the maintainer was paired with the work of the tinker, repairer and inventor. In this regard, information was precise, and there was no storytelling. Information took the form of lists with specifications of parts, diagrams, instruction manuals and technical drawings. Every job started in the toolbox with the selection of the right tools. Taking the vernier caliper out of its pale green leather pocket was the first step of any job.

There is a spectrum of maintenance that starts with regular cleaning, goes on to repair and ends up with the scrapping of parts for a new continuum. Maintenance is part of the relationship with objects that enables them to last. Technical maintenance is routine consultation, while repair is life-saving surgery when function goes wrong.

Technical maintenance and repair are part of my upbringing due to my father. Working as a ship mechanic meant that there was no difference between maintaining a part or an entire infrastructure, as both are determinants of good functioning of the system. At home, oiling a sewing machine, defrosting the fridge, changing the gas hose, repairing any broken appliance and so on were just normal aspects of daily life. The work of the maintainer was paired with the work of the tinker, repairer and inventor. In this regard, information was precise, and there was no storytelling. Information took the form of lists with specifications of parts, diagrams, instruction manuals and technical drawings. Every job started in the toolbox with the selection of the right tools. Taking the vernier caliper out of its pale green leather pocket was the first step of any job.

I remember a time when I used to peek to the side of the TV, curious to see where the cartoons were coming from. My curiosity was never satisfied, but it was rather transformed when the TV broke. I was amazed by looking at the interior of the TV housing and having my father explaining how all those components interacted for the TV to work as it should. More incredible was how the substitution of the blown fuse, a tiny, cheap component that would render that entertainment box obsolete, was able to prolong its life by fifteen years. Soon after, I started disassembling my toys, eager to tweak them.

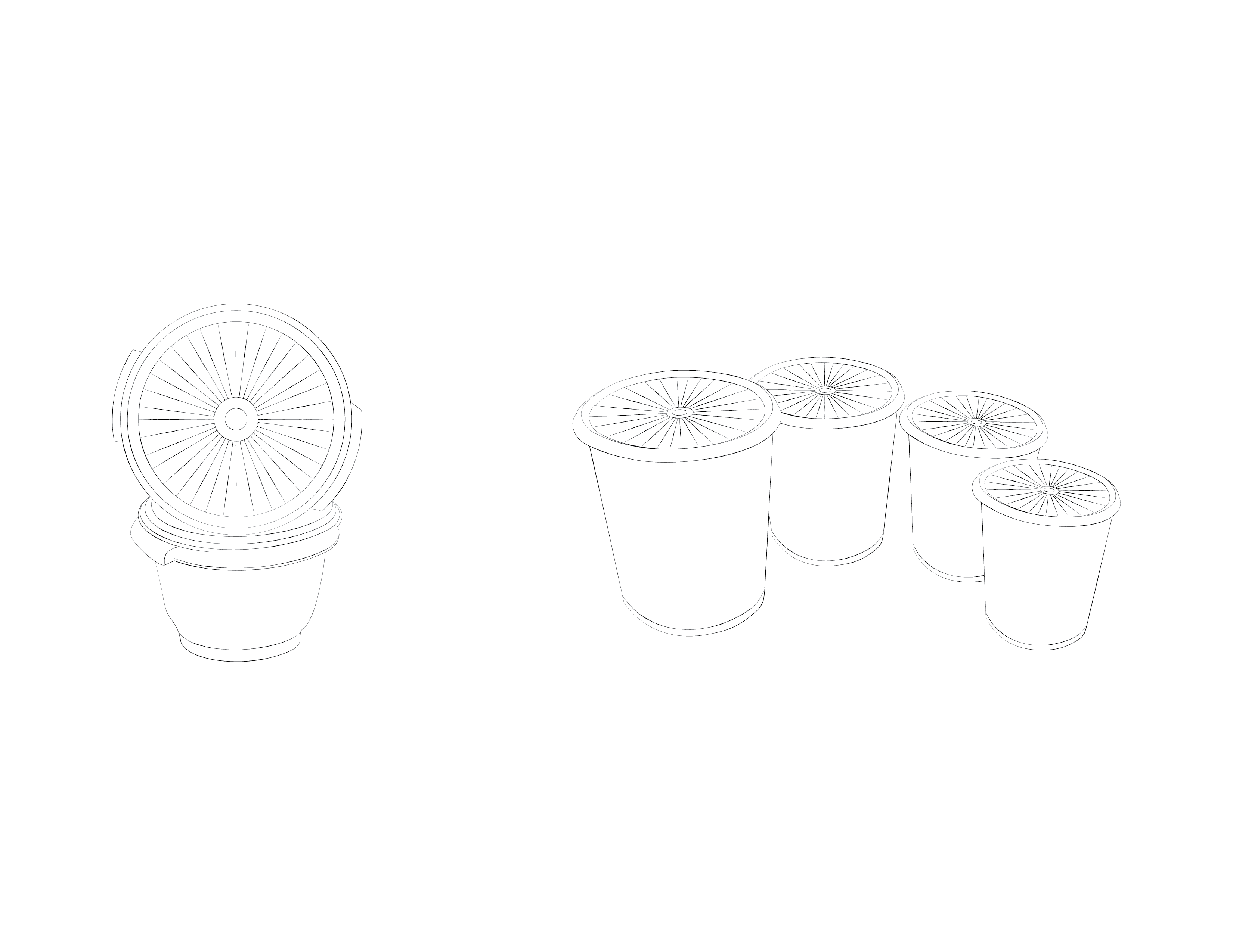

It is always fascinating to be able to transform the state of an object into something else – from the broken to the fully functional; creating something from scratch that would never exist otherwise or even observing the small intricacies that come into play, whether in physical or chemical changes. It can be the slight change that occurs when sanding what was rough into a smooth feeling. Or it can be when using a substance to clean, lubricate, aggregate, lock or create friction to achieve a predefined goal. In this regard, I have found equally appealing observing my mother heating a frying pan with water to loosen the grease as my father mixes a catalyst and resin to achieve the reverse effect in a repair. Beyond the domain of physical and chemical properties, transformation can happen by reframing the understanding of a thing by using it in a different setting. I term this ‘transformation of meaning’, like that old piece of wood that became a children’s stool that has lasted until today and is always painted in the same colour as the doors in the apartment, or the new space configurations allowed by replacing all the electric radiators in the apartment because the children put coloured pencils inside them. These transformations are just part of an organic conversation with materials, objects and spaces leading to new uses and possibilities that vary according to the need and availability of what can be used as a resource.

These described relationships, both with people and objects, are deeply rooted in Cape Verdean culture. By crossing the fact that my parents are islanders with their distinct personalities, I found myself trying to summarise their symbiotic relationship with the world and their respective worldviews. On the one hand, my mother’s extroversion, relying on disseminating information orally to relatives around the world, was based in one place – the home. On the other hand is my father’s introversion – relying on precise information and, as a seaman, travelling around the world.

My mother knows many places in the world by the stories she hears and passes on. She travels everywhere by contacting relatives in different places and time zones. To my father, the world is known and presented by latitudes and longitudes, together with geographical descriptions, always from the point of view of an approximation from the sea to the land. The stories he tells me are not about family members but rather about moments in twentieth century history experienced firsthand. These are everyday stories that explain how being an African man around the world was, like not being able to join colleagues for a beer in Houston because of racial segregation in the 1970s or in the 1980s in South Africa, due to apartheid.

I like thinking that there is a cumulative body of knowledge and practices that, more than being passed on, are interpreted and morphed into something else from generation to generation and from individual to individual, adapted to context according to self-idiosyncrasies. The one my parents transmitted to me is of many philosophies of African design that live despite the diaspora. I believe maintenance is at the core of such philosophies, and as said before, there is a spectrum of activities within maintenance. They all concur with prolonging life, provide a source for ongoing reflection and require your positive action to achieve favourable states of a dynamic system that constantly evolves through time whether you want it or not. Even though complementary, the work of my mother and that of my father embrace different ranges of such a spectrum. So how have I transformed such knowledge transmitted by my parents? For me, cleaning enables me to organise thoughts and provides a feeling of control over the space. It is a coping mechanism, a sport, informal mindfulness and a strategy to think within context. It allows for reviving memories of the past and sorting what still has meaning and is important to keep. It enables me to establish priorities for the present and the future and design a desirable future based on an assessment of a visible end result.

Maintenance is a work of care for continuing to preserve the dignity of things and their functionality. It also enables me to weigh the value of resources and the amount of work required, as well as assess real needs from time to time. It is systematic thinking in practice. It is a basis for designing better which emphasises the need to think about multiple use(r)s and lifecycles, as well as consider time, the decay of components and their value as important constraints.

It is always fascinating to be able to transform the state of an object into something else – from the broken to the fully functional; creating something from scratch that would never exist otherwise or even observing the small intricacies that come into play, whether in physical or chemical changes. It can be the slight change that occurs when sanding what was rough into a smooth feeling. Or it can be when using a substance to clean, lubricate, aggregate, lock or create friction to achieve a predefined goal. In this regard, I have found equally appealing observing my mother heating a frying pan with water to loosen the grease as my father mixes a catalyst and resin to achieve the reverse effect in a repair. Beyond the domain of physical and chemical properties, transformation can happen by reframing the understanding of a thing by using it in a different setting. I term this ‘transformation of meaning’, like that old piece of wood that became a children’s stool that has lasted until today and is always painted in the same colour as the doors in the apartment, or the new space configurations allowed by replacing all the electric radiators in the apartment because the children put coloured pencils inside them. These transformations are just part of an organic conversation with materials, objects and spaces leading to new uses and possibilities that vary according to the need and availability of what can be used as a resource.

These described relationships, both with people and objects, are deeply rooted in Cape Verdean culture. By crossing the fact that my parents are islanders with their distinct personalities, I found myself trying to summarise their symbiotic relationship with the world and their respective worldviews. On the one hand, my mother’s extroversion, relying on disseminating information orally to relatives around the world, was based in one place – the home. On the other hand is my father’s introversion – relying on precise information and, as a seaman, travelling around the world.

My mother knows many places in the world by the stories she hears and passes on. She travels everywhere by contacting relatives in different places and time zones. To my father, the world is known and presented by latitudes and longitudes, together with geographical descriptions, always from the point of view of an approximation from the sea to the land. The stories he tells me are not about family members but rather about moments in twentieth century history experienced firsthand. These are everyday stories that explain how being an African man around the world was, like not being able to join colleagues for a beer in Houston because of racial segregation in the 1970s or in the 1980s in South Africa, due to apartheid.

I like thinking that there is a cumulative body of knowledge and practices that, more than being passed on, are interpreted and morphed into something else from generation to generation and from individual to individual, adapted to context according to self-idiosyncrasies. The one my parents transmitted to me is of many philosophies of African design that live despite the diaspora. I believe maintenance is at the core of such philosophies, and as said before, there is a spectrum of activities within maintenance. They all concur with prolonging life, provide a source for ongoing reflection and require your positive action to achieve favourable states of a dynamic system that constantly evolves through time whether you want it or not. Even though complementary, the work of my mother and that of my father embrace different ranges of such a spectrum. So how have I transformed such knowledge transmitted by my parents? For me, cleaning enables me to organise thoughts and provides a feeling of control over the space. It is a coping mechanism, a sport, informal mindfulness and a strategy to think within context. It allows for reviving memories of the past and sorting what still has meaning and is important to keep. It enables me to establish priorities for the present and the future and design a desirable future based on an assessment of a visible end result.

Maintenance is a work of care for continuing to preserve the dignity of things and their functionality. It also enables me to weigh the value of resources and the amount of work required, as well as assess real needs from time to time. It is systematic thinking in practice. It is a basis for designing better which emphasises the need to think about multiple use(r)s and lifecycles, as well as consider time, the decay of components and their value as important constraints.

Mário Barros is an Industrial Designer graduate and a PhD in Design, both from the University of Lisbon in Portugal. He has taught and researched in Portugal and Vietnam, prior to working in Denmark.

His research addresses design problems taking interconnections and evolution over time as cornerstones of reasoning. Product morphology is the main research interest and it unfolds as methods for generative design amenable for computation and the assessment of existing designs. In this respect, the specific focus is the examination of the evolution of design languages and the study of product architecture to enable repairability.

︎ @ _milbarros_

︎ @milbarrosMB

︎ Mario Barros Milbarros

︎ Mario Barros

His research addresses design problems taking interconnections and evolution over time as cornerstones of reasoning. Product morphology is the main research interest and it unfolds as methods for generative design amenable for computation and the assessment of existing designs. In this respect, the specific focus is the examination of the evolution of design languages and the study of product architecture to enable repairability.

︎ @ _milbarros_

︎ @milbarrosMB

︎ Mario Barros Milbarros

︎ Mario Barros